The countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have important destinations to restore their degraded landscapes.

The loss of forest was a decades of problem because the region lost almost 15 million hectares of trees (1.2% of the total amount) from 2015 to 2023. However, 18 countries have signed over 50 million hectares of mined and failed country as part of the 20×20 initiative as recognition of the importance of forests for humans and natures.

How is the countries, at the age of five, to achieve the goal?

Measuring progress in the restoration has long been a difficult task, since lack of and credible data have a lack of and credible data. For the first time, new satellite data can “see” from year to year, in which trees grow where they stay and where they disappear.

This data creates from the University of Maryland and enable us to determine the dynamics of the tree coverage in Latin America from 2015 to 2023. It is not a perfect proxy for measuring the recovery progress – satellites cannot determine whether tree coverage gain is due to planned restoration, natural re -growing or industrial plants.

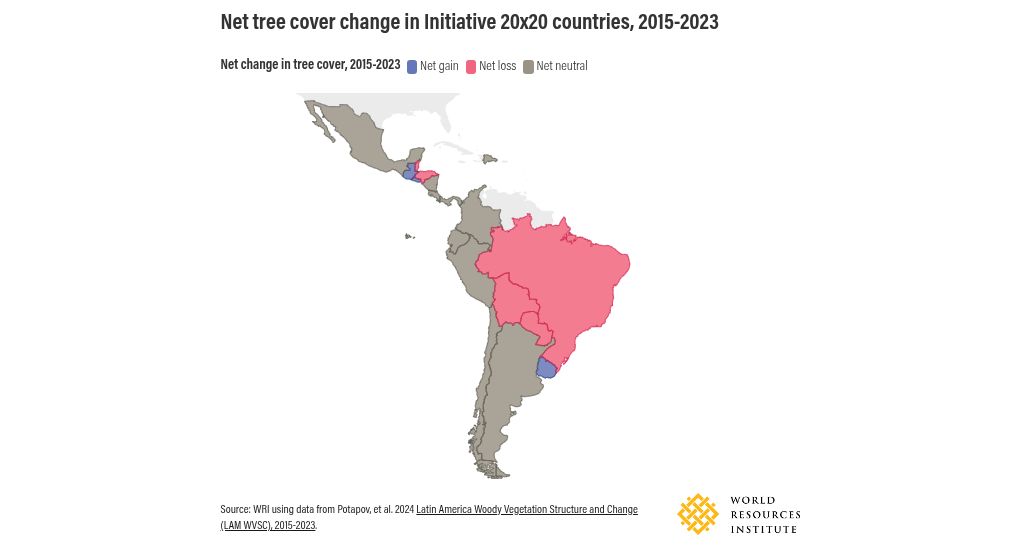

The data show that Latin America has lost more tree coverage overall than they won from 2015 to 2023, progress compared to historical trends. From the 18 countries that took part in the 20×20 initiative, three countries won tree cover from 2015 to 2023, 10 remained neutral and five experienced losses.

But only looking at the amount of tree coverage that a country had in 2023 compared to 2015 does not tell the entire history. The dynamics of the annual changes in the tree coverage and in which these changes result in a lot of progress in restoration and maintenance. In some countries, for example, the profits of tree covering mainly came from increased plantations that do not always benefit the environment.

Here are five important findings from the data:

1) The tree covering is very stable from year to year, but fluctuates considerably in others.

With the new data we can see whether there is more, less or the same amount of tree coverage in 2023 in 2015. Our analysis shows that 13 of the 18 examined countries had about the same or more tree covering compared to 2015 in 2023.

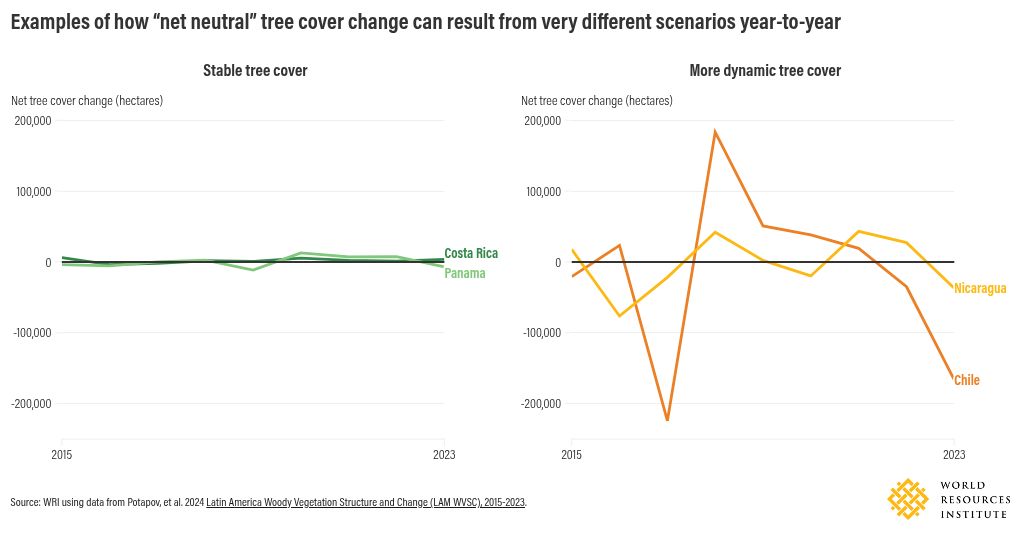

However, this “network -neutral” Satus could result from very different scenarios: This could mean that the tree coverage remained largely unchanged in the course of the period; Or it could mean that large parts of the tree covering were lost, but then replaced elsewhere by an equivalent amount of profit.

With regard to the health of ecosystems, unchanged tree covering is better. This means that the forests of the old forests remain in order to offer plants and animals habitat, protect carbon, protect the water supply and offer other critical services. As soon as the forests are lowered, it can take decades for new trees to become large enough to provide these services.

For example, tree covering in Costa Rica and Panama from 2015 to 2023 was very stable, with only minor changes changed from year to year. In Chile and Nicaragua, the tree covering fluctuated from hectares from year to year, although the total amount of tree covering the countries in 2023 was roughly the same as in 2015.

These patterns reflect different dynamics. Chile, Nicaragua and the other countries in which tree covering is more dynamic have more plantations or “working” forests that are constantly harvested and restored, as well as higher cases of disorders such as fire or hurricanes, which naturally cause loss. The stability in Costa Rica and Panama indicates larger forest protection and less natural or humans caused by humans.

2) The tree covering extends to farms.

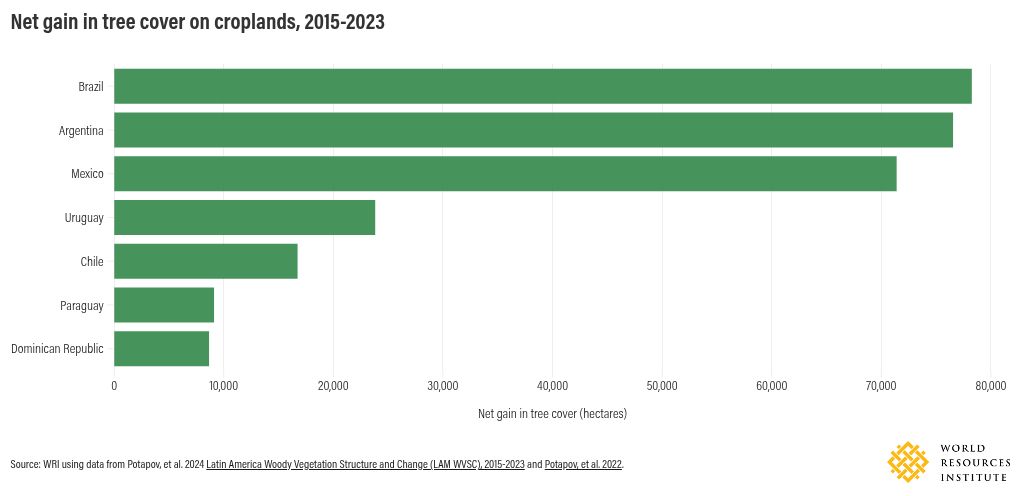

Proportional Croplands recorded the highest net profits in tree coverage in any other landscape – almost 300,000 hectares or 24% compared to the tree coverings in 2015. The majority of this net profit focused on seven of the 18 countries examined: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Paraguay and Uruguay.

Although we cannot precisely determine what is going on in all of these cases, part of these profits comes from Agroforst and sustainable agriculture, including the integration of trees with harvesting to stabilize floors and increase productivity. However, most are likely to be attributed to the plantation device, for example on wood, rubber and oil palm. For example, Uruguay recorded a considerable amount of tree covering from 2015 to 2023, but it mainly occurred in the form of plantations.

While plantations can be advantageous if you remove the drainage pressure from the natural forests or improve the productivity of formerly degraded areas, you can also be harmful. If plantations, for example, replace natural forests with monocultures or are planted in areas that do not support forests such as indigenous grass landscapes, they can affect biological diversity, water availability and soil quality. These types of plantations are usually not taken into account as a restoration.

3) Many cities are becoming more environmentally friendly.

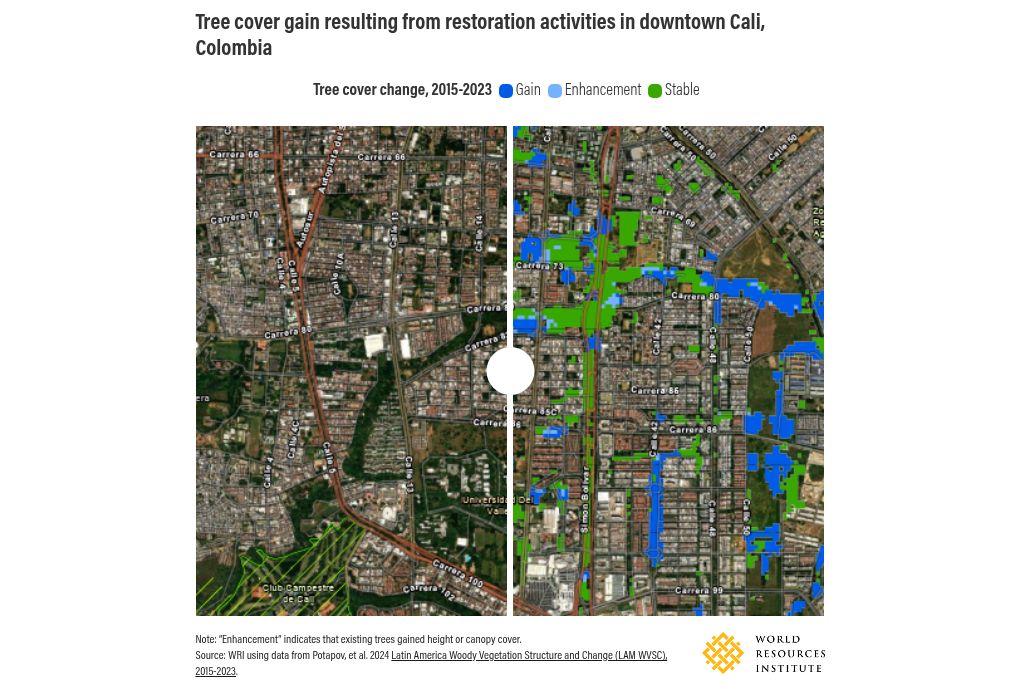

Two thirds (12 out of 18) of the examined countries had a net covers in cities and near other built infrastructure, such as: B. along important streets and highways. Trees in urban areas offer cooling color, clean the air by filtering pollutants and creating inviting rooms in which people can enjoy time outdoors.

Two countries – Nicaragua and Colombia – led the way with the “green” areas with the net covers of 3% or 2%. For example, Cali, Colombia, was recently certified by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the Arbor Day Foundation of the United Nations as one of the “tree cities of the world” due to its network of urban forests and green areas within the city that promote biodiversity and improve quality of life for the quality of life.

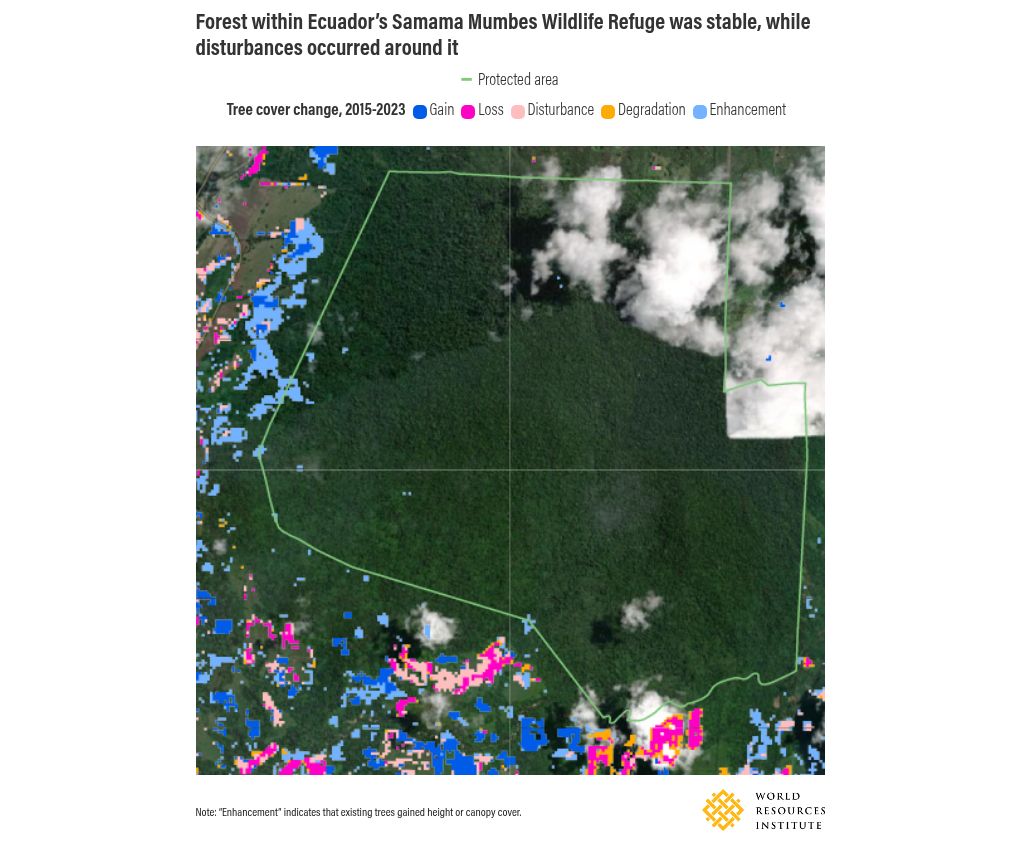

4) Protection areas are often the best way to get forests – if they are effectively managed.

In all countries, 95% of the tree covering within protected areas was stable – which did not occur any profits, losses or disorders between 2015 and 2023. This shows that the establishment of protected areas is often an effective way to maintain forests.

Peru, Ecuador and Chile had the most stable forests in their protected areas, with more than 98% of the inner forest area showing no change.

In three countries of Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala-War, however, tree covering in protected areas is more unstable than other areas, of only 75%-80%. The net loss of forest in these countries was actually higher within protected areas than outside. While some of the observed forest losses are due to natural disasters, the guidelines and their enforcement deserve a closer look in these nations.

5) National politics for the incentive to the restoration shows positive results.

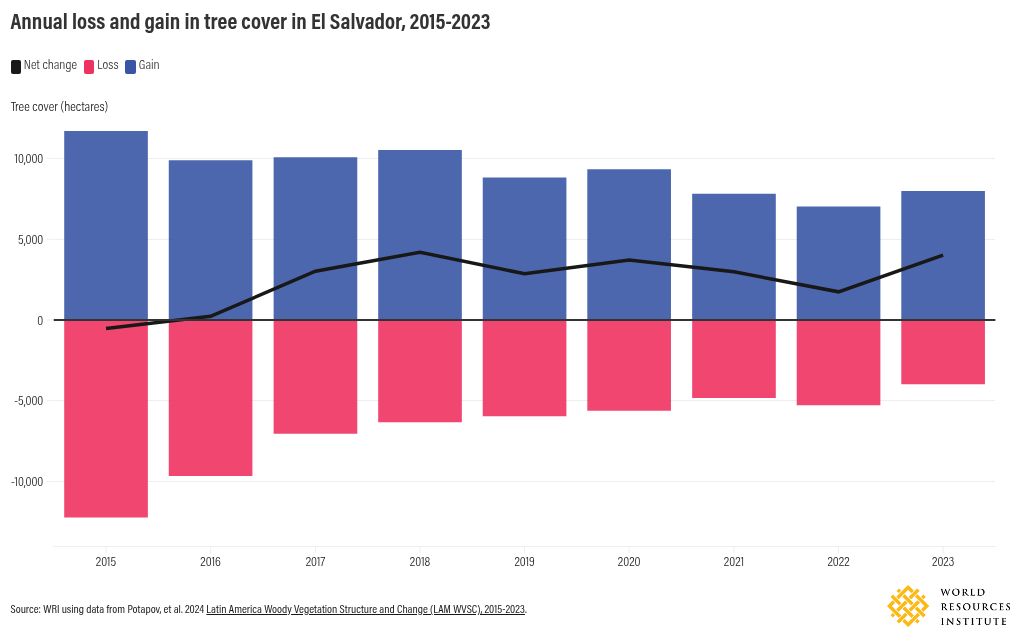

El Salvador and Guatemala have implemented unique, state -managed programs that prioritize both the restoration and financing of the financing. Data indicate that these programs have a positive impact on winning the tree coverage.

El Salvador was the only one of 18 countries in which net tree covers were achieved in all land types, including internal protection areas. The deforestation has been a problem in El Salvador for decades. In the 1970s, everyone lost to 6% of its local forest cover. Although the country started with less tree coverage in 2015 than others, the data clearly show that trees come back everywhere. These positive trends are at least partially due to the political support for the restoration, such as the program for ecological incentives and incentives from the government of 2022, which rewards sustainable activities and discourages the deterioration in landscape. Recent guidelines, such as the 2024 environmental assessment system, to better evaluate the effects of human activities on the environment and the national program 2025 to restore ecosystems and productive landscapes, should further promote recovery.

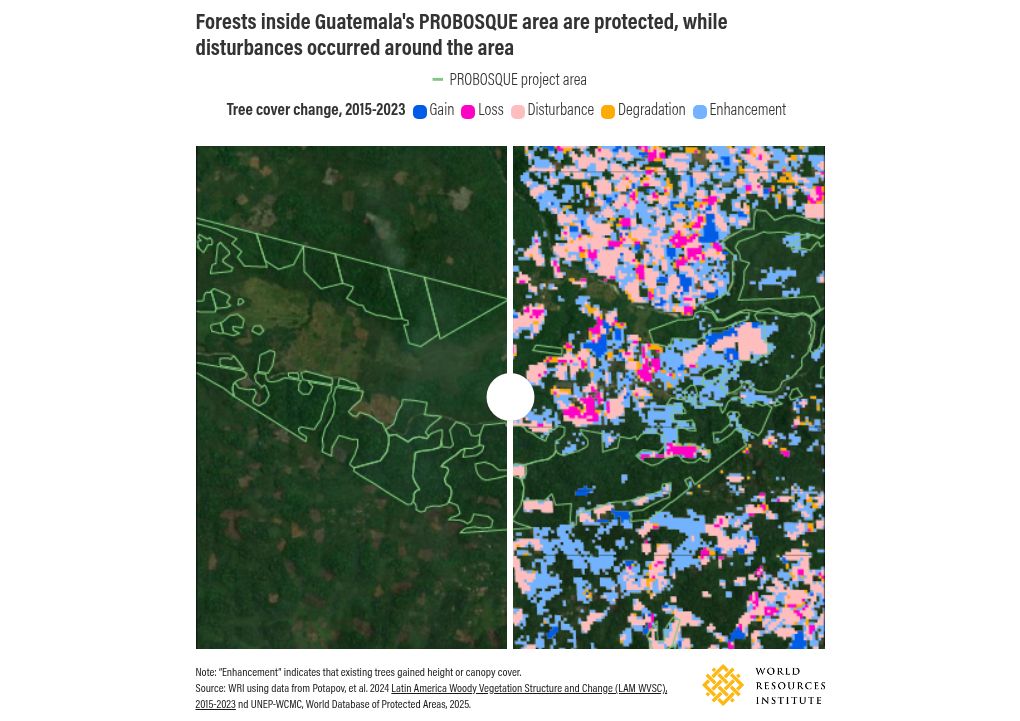

Guatemala has also achieved positive results. The Guatemaltean government implemented its Probosque program in 2017 and financed the small farmers to save, plant and maintain trees in their country. The analysis of the mapped ProBosque positions defined between 2017 and 2020 shows that 20,600 hectares of tree covering were stable and from 2023 there was a net profit of 830 hectares. Continuation of the Probosque incentive program together with the associated mapping and surveillance could help to further support farmers and trees.

Use data to inform the progress and to promote more recovery

With this data, national and local governments can better identify successful programs or where changes are required. In Guatemala, for example, Probosque contributed to improving tree covering in the farmers, the forests in the country's protected areas are still lost. Since the data shows the larger image of trees across the country, it can be used to monitor and inform guidelines and incentives.

Improved documentation about where the restoration takes place is also of essential importance. We now have the data to change, but we need more information about where we can evaluate the progress against recovery goals and determine whether the restoration efforts actually generate healthier and more resistant ecosystems – which is ultimately the goal. By combining this data with documentation on site, people can be better assessed where the countries are in the restoration of their deteriorated landscapes.

In the 10 years of the 20×20 initiative, it is an important lesson that many actors and a coalition of projects, guidelines and incentives work together to build up the swing of success. The improvement of access and the availability of data for monitoring changes is another tool that can help support sustainable landscapes in the future.