In the absence of stronger federal regulation, some states have started to regulate apps that offer “therapy” because more people turn to artificial intelligence for advice on mental health.

But the laws that were all passed this year do not fully deal with the rapidly changing landscape of AI software development. And app developers, political decision -makers and lawyers for mental health say that the resulting patchwork of state laws is not sufficient to protect users or to hold the creators of harmful technology.

“The reality is that millions of people use these tools and do not return them,” said Karin Andrea Stephan, CEO and co-founder of the Chatbot app of mental health.

___

Note from the publisher – this story contains the discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know need help, you will find the national suicide and crisis rescue line in the USA by calling or sending 988. There is also an online chat under 988lifeline.org.

___

The state laws pursue different approaches. Illinois and Nevada have banned the use of AI to treat mental health. Utah has set certain limits therapy chatbots, including the demand that you protect users' health information and clearly disclose that the chatbot is not a human being. Pennsylvania, New Jersey and California also consider ways to regulate AI therapy.

The effects on the users vary. Some apps have blocked access to states. Others say they do not make any changes because they are waiting for more legal clarity.

And many of the laws do not deal with generic chatbots such as chattgt that are not expressly marketed for therapy, but are used by an inextricable number of people. In terrible cases, these bots have attracted complaints in which users have lost reality under control or took their own lives with them after the interaction.

Vaile Wright, which monitors the innovation of health care at the American Psychological Association, agreed that the apps could meet a need, and noticed a nationwide lack of providers of mental health, high costs for care and uneven access for insured patients.

Chatbots for mental health that are rooted in science, created with experienced contributions and monitored by humans could change the landscape, said Wright.

“This could be something that helps people before they come to the crisis,” she said. “This is currently not on the commercial market.”

Therefore, federal regulation and oversight are required, she said.

At the beginning of this month, the Federal Trade Commission announced to open inquiries about seven Ki chat bot companies -including the parent companies of Instagram and Facebook, Google, Chatgpt, Grok (the chatbot to X), character.ai and Snapchat, such as “measuring, testing and monitoring potentially negative effects of this technology on children and teenagers”. And the Food and Drug Administration convened an advisory committee on November 6th to check the generative AI-capable psychiatric devices.

Federal authorities could consider restrictions on how chatbots are marketed, limited addictive practices, disclosure to the users require that they are not medical providers, have to pursue companies and have to be at risk of suicide, and legal protective measures for people who report poor practices of companies.

Not all apps have blocked access

From “Companion Apps” to “AI therapists” to “mental wellness” apps, the use of AI in mental health care is diverse and difficult to define, let alone write laws.

This has led to different regulatory approaches. Some countries, for example, aim at accompanying apps that are only designed for friendship but do not go into mental health care. The laws in Illinois and Nevada prohibit products that claim to enable psychological treatment and face fines up to $ 10,000 in Illinois and $ 15,000 in Nevada.

But a single app can also be difficult to categorize.

Stephan von Earkick said, for example, a lot about the law of Illinois was still “very muddy”, and the company has no limited access there.

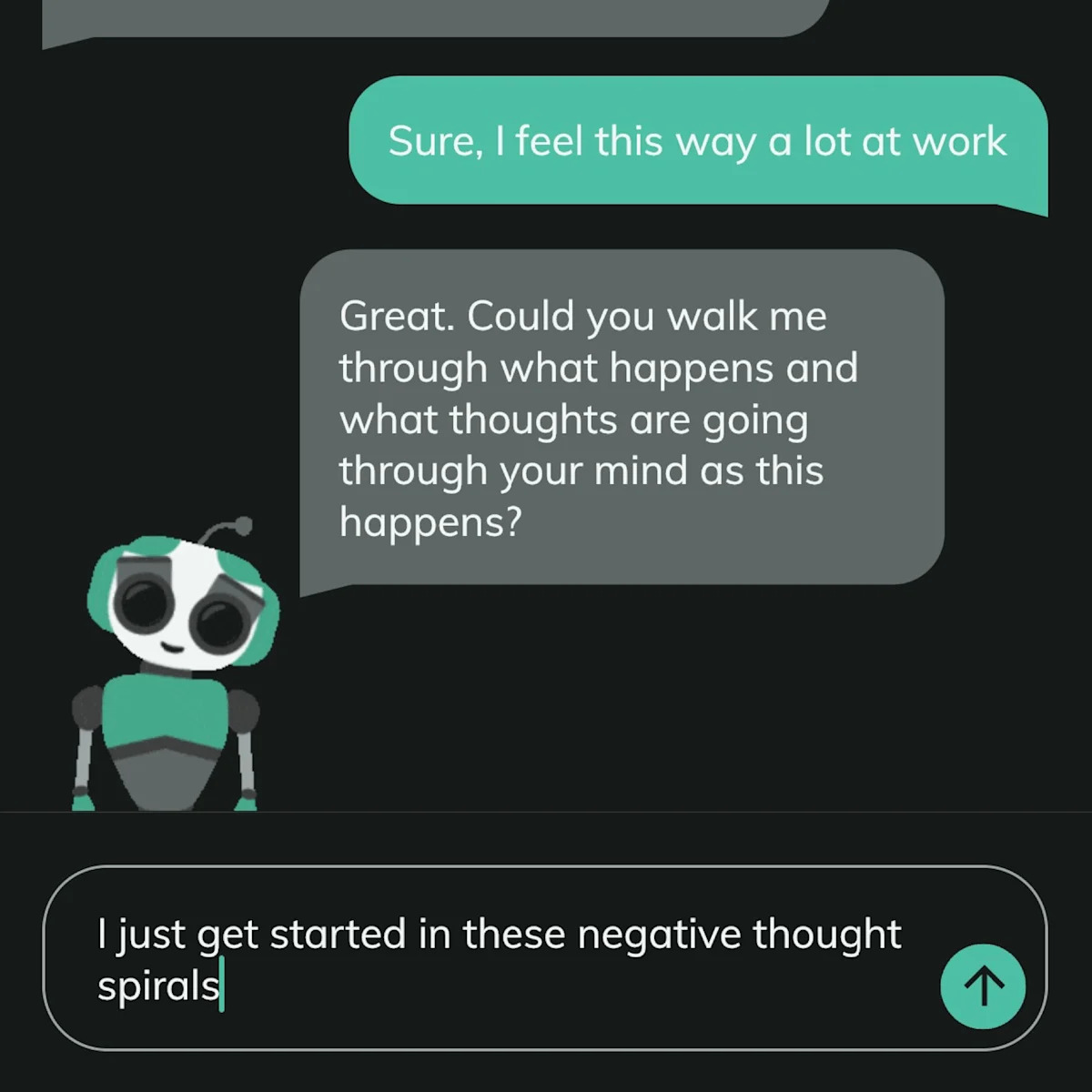

Stephan and her team first called their chat bot, who looks like a cartoon panda. As a user, use the word in reviews, accepted the terminology so that the app was displayed during search queries.

Last week they withdrew with therapy and medical terms. Earkick's website described its chatbot as “its sensitive AI consultant who is equipped for the support of your mental health trip, but now it is a” chat bot for self -sufficiency “.

Nevertheless, “we don't diagnose,” said Stephan.

Users can set up a “panic button” to call up a trustworthy loved one when they are in the crisis and the chat bot “nudge” the users to look for a therapist if their mental health deteriorates. But it was never designed in such a way that it was a suicide prevention app, said Stephan, and the police would not call if someone said about the thought of self-harm.

Stephan said she was glad that people look at AI with a critical eye, but concerned about the ability of the states to keep up with innovation.

“The speed with which everything develops is massive,” she said.

Other apps blocked the access immediately. If Illinois users download AI therapy -app ASH, a message asks you to send your legislators by e -mail and argue that “misguided laws” have banned apps such as ASH while leaving non -regulated chatbots that intend to regulate it free of charge to cause damage. “

A spokesman for ASH did not respond to several inquiries for an interview.

Mario Treto Jr., Secretary of the Ministry of Finance and Professional Regulation in Illinois, said that the goal was ultimately certain that licensed therapists were the only therapy.

“Therapy is more than just one word exchanges,” said Treto. “It requires empathy, it requires clinical judgment, it requires ethical responsibility, of which no AI can really replicate now.”

A Chatbot company tries to completely replicate the therapy

In March, a team based in Dartmouth University released the first known randomized clinical study of a generative AI chatbot for the treatment of mental health.

The aim was to treat the chatbot, called Therabot, to treat people in whom fear, depression or eating disorders were diagnosed. It was trained on vignettes and transcripts that were written by the team to illustrate an evidence -based answer.

The study showed that users assessed Therabot similar to a therapist and, after eight weeks, had a sensible symptoms compared to people who did not use them. Every interaction was monitored by a person who intervened when the reaction of the chatbot was harmful or not evidence -based.

Nicholas Jacobson, a clinical psychologist whose laboratory heads research, said the results showed promise at an early stage, but larger studies are necessary to prove whether Therabot works for a large number of people.

“The room is so dramatic that I think that the field has to be much greater caution that has just happened,” he said.

Many AI apps are optimized and developed for the commitment to support everything that users say instead of finding out people's thoughts as therapists do. Many go the line of camaraderie and therapy, although the therapists of the intimacy limits would not ethically do.

The Therabot team tried to avoid these problems.

The app is still testing and not widespread. But Jacobson is worried about what strict prohibitions will mean for developers who pursue a careful approach. He noticed that Illinois had no clear way to provide evidence that an app is safe and effective.

“You want to protect people, but the traditional system is really a striking people at the moment,” he said. “So if you try to stick to the status quo, it is really not what you can do.”

Supervisory authorities and supporters of the laws say that they are open to changes. However, today's chatbots are not a solution to the lack of psychiatric providers, said Kyle Hillman, who, through his belonging to the national association of social workers, campaigned for the invoices in Illinois and Nevada.

“Not everyone who is sad needs a therapist,” he said. But for people with real mental health problems or suicide thoughts: “Tell them:” I know that there is a lack of workforce, but here is a bot ” – that is such a privileged position.”

___

The Department of Health and Science Department of Associated Press receives support from the Department of Science Education of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is only responsible for all content.