Chances are you've seen Summer Coleman's graphic design or branding work. She designed the eye-catching, glossy menu and window graphics at Bronzeville Winery. She designed the flowing blue branding for Lieutenant Governor Juliana Stratton; an updated, comprehensive logo for the Brave Space Alliance; and the vibrant design of the Hazel Crest Creative Arts Center in Hazel Crest, Illinois. She made the CTA ad for artist Amanda Williams' epic Redefining Redlining project. But you may not be familiar with her artistic practice, which has recently taken a new direction.

Courtesy of Bronzeville Winery

Although the Chicago native received her bachelor's degree in studio art from the University of Illinois Chicago, she has spent most of her career – about two decades – in the design field. The career choice was largely due to the time (and financial) constraints that come with being a parent. Coincidentally, it was her role as caretaker that led to her new series of soft sculptures. Coleman is part of the 2024-25 Wild Yams seed cohort, an artist residency for Black mothers and caregivers. At the beginning of the stay, Coleman decided to purchase a sewing machine and reacquaint himself with the art of sewing.

Summer Coleman

summercoleman.com

“This work is about my grandmother and my memory of her time as a seamstress,” Coleman said. The artist recalled sitting at a table with her grandmother, a seamstress from the community who raised her, not paying much attention to the sewing lessons she was taking. “None of it is quite perfect,” Coleman said, pointing to the various sculptures in progress in her studio. “But that’s the point.”

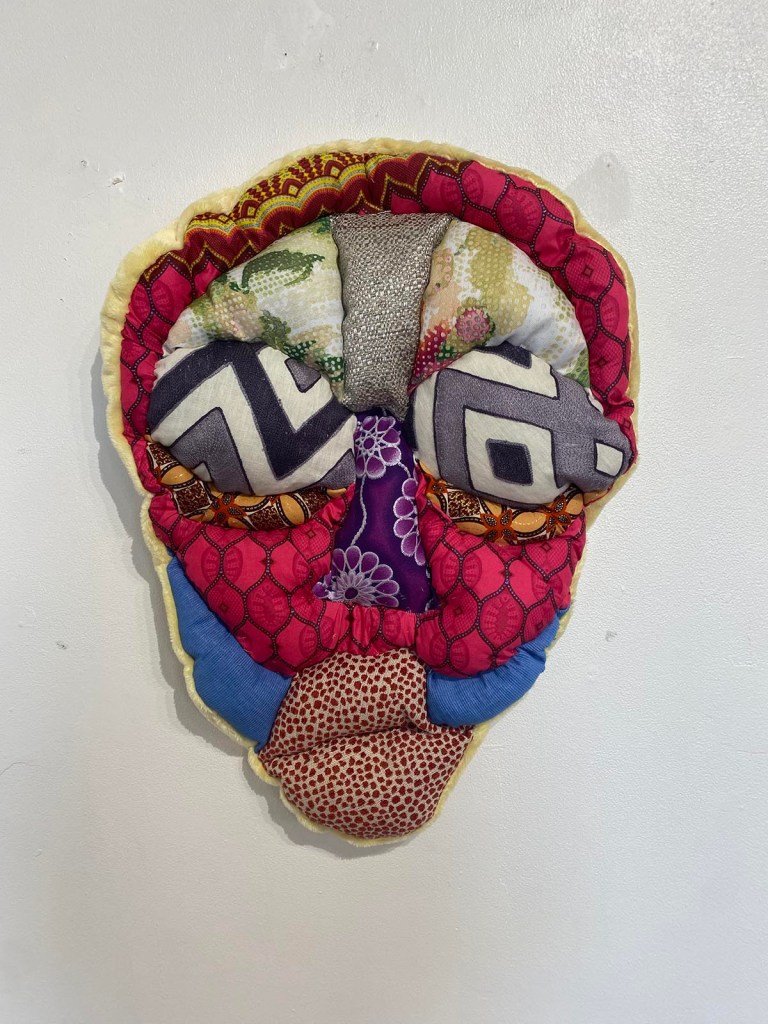

Coleman's series is inspired by contemporary conversations around topics such as religion and fertility and seeks to reclaim stolen narratives about African religions. “A lot of people don’t remember or even know the history of these things,” she said. “So we’re just trying to give ourselves back our history.” Using recycled or reclaimed fabrics in bold colors and vibrant patterns, Coleman's sculptures reference African fertility goddesses and deities. Some are oversized faces hanging on the wall, others are full-figured bodies. And Coleman's deities aren't just for looking at – their viewers can interact with them.

Courtesy of the artist

“God – he’s usually up there on an altar,” she said. “It's a little different with dolls and things like that. . . . You can touch them, pose them, hug them, do different things.”

She showed me the beginning of a giant Ashanti Akua'ba doll, traditionally used as a fertility charm, sewn from scraps of fabric and double stuffed with soft stuffing. Its head is made up of bands of bright orange fabric that define large patches with blue, black and purple patterns. When finished, it will be about two to seven feet long and will stand on the ground. Visitors will be able to interact with the doll at an upcoming Wild Yams exhibit at Co-Prosperity, scheduled for mid-to-late 2026.

For Coleman, it is important not to use new materials, citing the ever-worsening problem of used clothing in the West, which is causing massive environmental problems in Africa, particularly in Ghana, where around 15 million pieces of used clothing are received every week. To design one of her sculptures, Coleman sketches out a design and then tries to put fabrics together to find what goes well together. For them, figuring out how to use small or irregularly shaped pieces is a particularly exciting challenge. “Anyone can use bolts of fabric,” she said.

Her design background also helps drive the new sculptures as she thinks about how to share her research and additional context on the pieces with her audience. She's thinking about making a zine so people can continue to learn about the dolls.

She credits Wild Yams with helping her get back into sewing. “Wild Yams is amazing,” she said. “This was the best residency of my life – and I didn't really know I could sew that well. So I thought, 'Okay, maybe this is something I could do.'”

Courtesy of the artist

Over the summer, the cohort spent a weekend at ACRE's residence in Wisconsin, working on their projects with their children. Coleman's daughter, an artist and photographer, didn't want to leave until a call from Wisdom Baty, founder of Wild Yams, changed her mind. “So much community care,” Coleman said.

When Coleman looks back on her twenty-plus years as an artist, she realizes that she has never sewn before. “I'm getting older – I hate to say it – I'm 46… And as I thought about my matriarch's story and thought about who raised me and what did I used to do? I love sewing. I've always wanted to get a sewing machine,” she said. When she was accepted into residency, she decided to give it a try. “I'm always sitting in front of my computer, so let's do something with my hands. Let's do something different. . . . I was pleasantly surprised. I thought, 'Okay.' These are the first things I did: Learn. So I remembered. That is the presence of it. I call them channels – I channel the memory of [my grandmother] with these.”