Above: A vacation home in the Valle de Guadalupe on Mexico's Baja Peninsula, designed by architect Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig with Matiz Estudio. Sculpture by Teodoro Huerta.

Valle de Guadalupe, at the northern end of Mexico's Baja Peninsula, is a brilliant desert basin whose sandy soil is the color of moondust. At night you feel like you're in a planetarium thanks to low humidity and minimal light pollution. It is fringed by mountains and bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the west, giving the valley a Mediterranean microclimate that, aided by irrigation, has produced a vibrant wine culture: it is Mexico's answer to Napa. Just two hours from San Diego, when the traffic gods smile, it has become a weekend getaway destination, with a quiet, haunting, almost otherworldly landscape, still rough around the edges, interspersed with vineyards and close to the beach, all set to a Norteño soundtrack.

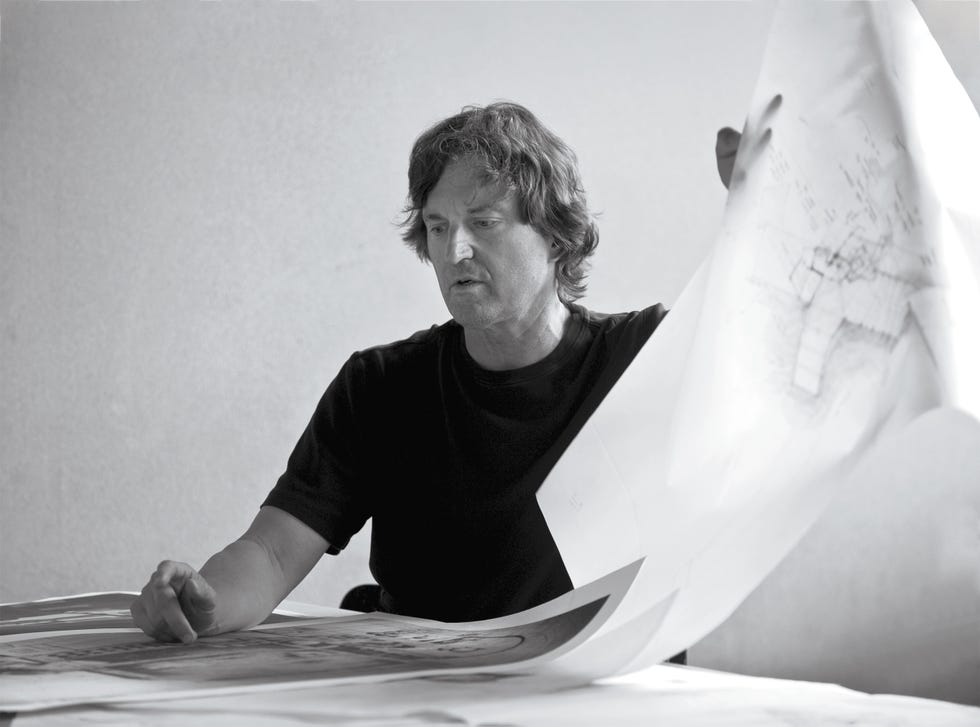

Seattle-based architect Tom Kundig had never heard of the region before traveling there several years ago. His first visit came as part of a road trip from Southern California with clients, a couple with two young children. Having road-tripped with Kundig myself (through the vast northern Utah region from Salt Lake City to the Bonneville Salt Flats), I know the excitement that comes from him when he ventures into new territory, especially when it's extreme or forbidding—the very places where Kundig, one of America's leading contemporary residential architects, loves to build. About his first encounter with the Valle de Guadalupe, he says: “I was so excited when I went to this new place. And when I went on a road trip there. This is a way to experience a landscape – so much better than flying.”

Kundig's enthusiasm turned to passion when the couple drove onto an unpromising dirt road and came across an abandoned, undeveloped piece of land. It was, as he says, “a blank sheet of paper,” the perfect tabula rasa on which to practice some design magic in crafting what would become El Grove: a welcoming desert compound for a growing family, right in the dusty heart of the Valle de Guadalupe.

Kundig, who recently turned 71, grew up not far from another high desert in Spokane, Washington. His Swiss-born father, Moritz Kundig, was an architect – which of course meant that young Tom was reluctant to become one himself. As a child, he studied with Harold Balazs, a sculptor from Mead, Washington, whose motto became, in a way, his own: “Transcend the Bullshit.” Between Balazs and his father, Kundig was steeped in the cutting-edge tradition, but he was also steeped in the Kustom Kulture: those souped-up hot rods from Southern Californians like Ed “Big Daddy” Roth and Von Dutch. He also absorbed the raw architectural language of Eastern Washington's agricultural and mining structures—nondescript, machine-like buildings that evoked American enterprise and industry.

Kundig brought these disparate strands together as he overcame his reluctance to follow in his father's footsteps, bringing a unique brand of bravado to architecture. In his personal life, he became known for dangerous ventures, such as skiing at high altitudes and tool-riding across Argentina on a BMW 1200.

He brought a similar fearlessness to his design work, creating boundary-pushing homes like the award-winning Chicken Point Cabin in Idaho, where he installed a 20-by-30-foot glass and steel wall that could be raised like a giant garage door with a few turns of a flywheel.

Such things became an early Kundig trademark. “There's always a certain playfulness in Tom's work,” says architectural historian and cultural entrepreneur Robert M. Rubin, who owns the modernist Paris landmark Maison de Verre, designed by Pierre Chareau in 1928. “It’s techno-surrealist in a way.”

But there is always nature, a lasting love. “The land,” emphasizes Kundig, “is more important than the architecture.” It is this grounded perspective in the truest sense of the word that has made him a counterweight to the star architect craze of the 21st century. He's not concerned with branding, blobs or asymptotes. There is no Howard Roark glorification. “He acts like a normal architecture buff,” Rubin notes.

Kundig's buildings are understated yet lyrical, robust yet sophisticated, earthy yet ethereal. More than 460 of these residential wonders are included in his recently published work Complete houses (Monacelli), a comprehensive monograph of his global work with the firm Olson Kundig, which he co-directs with architect Jim Olson. This book will follow next year All worksin which non-residential projects are presented. (Full disclosure: I wrote the main essay for Kundig's 2020 book, working title, which included everything from wineries to skyscrapers.)

In the foreword to the latest book, Kundig writes about the “gentle dissolution of the ego under the weight of something limitless, ancient and enduring” – the eternal pleasure of the landscape. This is the experience at El Grove, where, as he says, “you have to go outside to go in.”

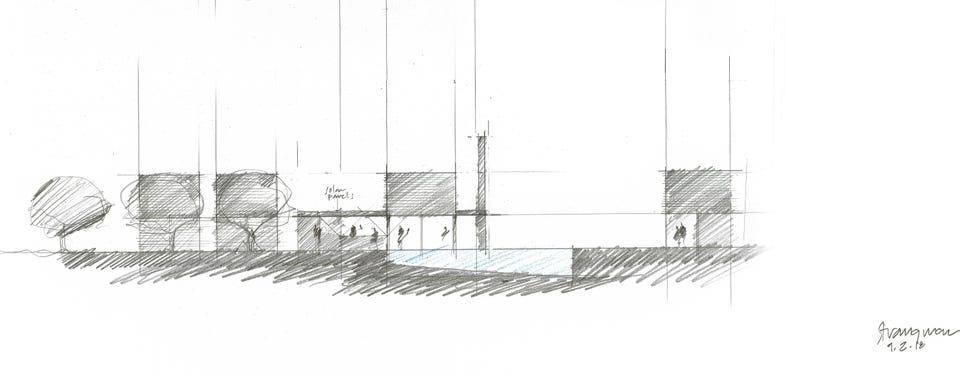

This is thanks to an ingeniously simple plan that divides the traditional elements of a home – the living area, the bedrooms – into separate structures connected by stepping stones studded with wild grasses. In his unpretentious way, Kundig calls them “huts”. There is a primary living cabin, with a modular kitchen, large dining table, turntable-mounted entertainment island with built-in speakers and a spacious floating fireplace; a cottage for the master bedroom; and two villa-like cabins for the children to accommodate future grandchildren. The architecture allows the house's residents to interact with nature.

“If you want to create a place in a beautiful landscape, you have to get involved with it,” says Kundig. “It allows you to experience the place instead of locking yourself in an air-conditioned box.” If the heat in the Valle is too much, there is a shady olive grove to hide in, not to mention a pond made from a Texas-style cattle tank located next to the main cabin and lined with lavender.

The buildings, with a total area of 2,900 square meters, are constructed of simple concrete cinder blocks. “It’s the perfect material for this landscape,” says Kundig. “Tough as nails and made from the earth.” The light gray hue gives the huts a muted aura: solid yet spooky. The interiors are made of simple Kundigesque plywood, providing a gentle feeling of comfort and refuge. “It’s about using common materials in unusual ways,” he says, “to make a place feel special.”

This story originally appeared in the November 2025 issue of Elle Decor. SUBSCRIBE