A local group called Traverse City Community Design is working to expand the boundaries of Traverse City's three historic districts – Central, Boardman and Downtown – and create new historic districts in Slabtown and Old Town. At least 51 percent of property owners must agree to become part of a historic district, a designation that limits the construction and design of homes but also preserves the neighborhood's character and increases property values, the group says.

Architects Suzannah Tobin and Ken Richmond presented the proposal at a meeting at the Central Neighborhood Association's Crooked Tree Arts Center last night. The duo will also discuss the concept with the Historic Districts Commission (HDC) – a board they both previously served on for many years – at the commission's lunch meeting today (Thursday) at the Governmental Center.

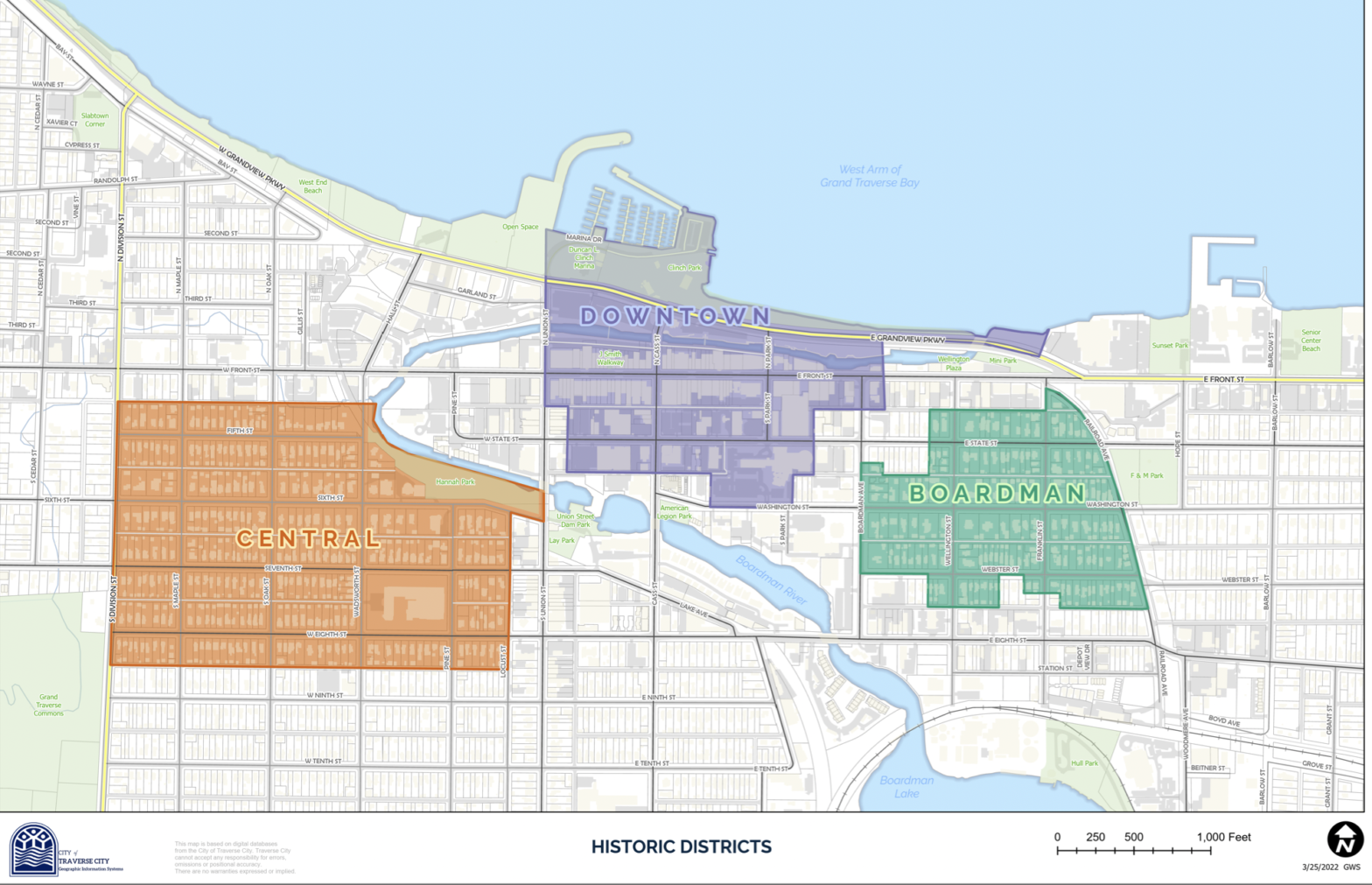

Traverse City has three existing historic districts (image, map), which are defined in the city ordinance as a designated area that “reflects elements of the city's cultural, social, economic, political or architectural history and is worthy of recognition and historic preservation.” . Central's boundaries are roughly defined by north of Fifth Street, Division Street, the alley between Eighth and Ninth Streets, and Locust Street. Downtown includes much of downtown between Union, Washington, Boardman and Grandview Parkway. Boardman covers an irregular area between Boardman Avenue, south of Webster Street, Railroad Avenue and north of State Street.

Both residential and commercial property owners in a historic district must contact the city's HDC for approval if they wish to perform certain work on their sites. This includes the construction of a new building, the relocation or demolition of a structure, and external changes or repairs that require a building permit. For example, changing paint colors or replacing shutters wouldn't require an inspection, but building a new porch or garage would. Seven members appointed by the City Commission sit on the HDC, whose membership must include at least one registered architect and two members nominated by preservation associations or historical groups.

In the Central and Boardman neighborhoods, historic district boundaries differ from neighborhood association boundaries—a difference that is particularly pronounced in Central. That's one reason Tobin and Richmond are pushing to expand the boundaries of the historic district from Central south to Griffin Street, reflecting neighborhood association lines. “The neighborhood itself is very clearly defined,” Tobin says. “We find it organic and distinctive.”

Tobin says she and Richmond have also heard numerous complaints over the years at HDC from people who were upset about the look or size of new developments downtown or in their neighborhoods and questioned how those projects were allowed to be built. “My answer was always the same: This building wasn’t in one of the historic districts,” Tobin says. Historic districts can help ensure that the patterns of neighborhood streets — the scale and layout of their homes and buildings — remain consistent, she says. This creates predictability and a “sense of place,” the architects believe, contributing to a sense of stability and higher property values.

Tobin says the city's recently adopted master plan – which sets building design standards for commercial developments as a long-term goal – and resident feedback in the city's ongoing new strategic action plan show that “people really care about urban design and protection.” “To be intentional about the character of downtown and neighborhoods.” Accordingly, “it feels like a really good time” to help neighborhoods understand their options for expanding their historic district boundaries or creating new historic districts, says Tobin.

However, not all owners want to voluntarily limit their own properties or limit their flexibility in renovation and design. The strange “gerrymandered” boundaries of the Downtown and Boardman historic districts reflect some property owners’ previous opposition to the designation, Tobin acknowledges. In Central Neighborhood, property owners outside the boundaries of the historic district have sometimes built modern homes, advocating design diversity as an important value alongside preserving historic charm on certain streets. Furthermore, the expansion or addition of historic districts could bring dozens or even hundreds of new properties in Traverse City under the HDC's purview, consolidating power in the hands of seven rotating individuals whose appraisal standards can sometimes fluctuate and be subjective or unclear – how Tobin You yourself will testify to it.

Still, Tobin believes the positive aspects of historic districts outweigh the negatives — and says certain steps, such as better defining the HDC's review standards, could further improve the process. “We need to be more objective and less subjective about what is expected,” she says. “There have to be clear guidelines to follow.” As an architect, Tobin emphasizes that she is neither against new developments nor against trying to cling to a predetermined idea of the past. “I think the word 'historic' scares people away and that means we have to keep everything exactly as it is,” she says. “That is not our intention. I'm not afraid of growth, but I want that growth to be respectful. It has to respect the context (of the neighborhood).”

Tobin says that while she and Richmond are holding community listening sessions and helping to move forward in the exploration process for the expansion, their goal is for neighborhoods to ultimately take the reins and, with support from Traverse City Community Design, take the lead take over. The city's ordinance outlines the process these neighborhoods must follow, starting with a petition signed by at least 20 percent of property owners within the proposed new boundaries. This petition follows an HDC study of the expansion area with a report submitted to the City Planning Commission, the Michigan Historical Commission and the State Historical Advisory Council.

From there, signatures must be collected from at least 51 percent of the property owners confirming their consent to remain in the historic district. The HDC must hold a public hearing within 60 days of receiving these signatures and then submit a final report to the City Commission within one year of the hearing. A City Commission vote will be held to approve and adopt the historic district boundaries. Overall, the process is expected to take about two years based on resources in the proposed district, according to Tobin and Richmond.