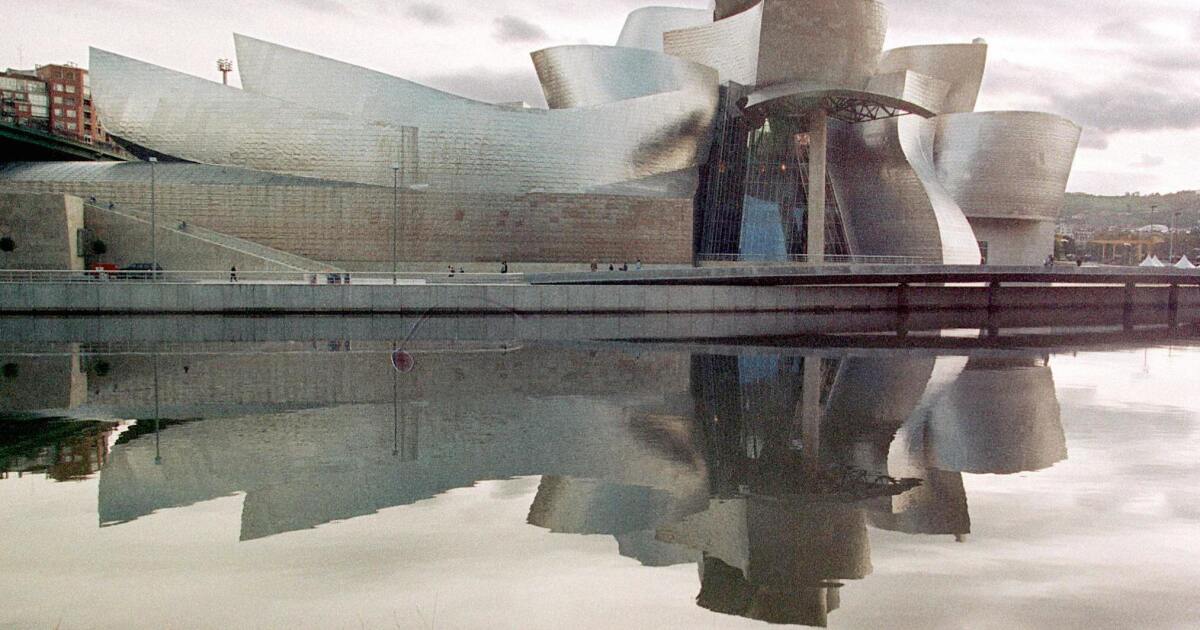

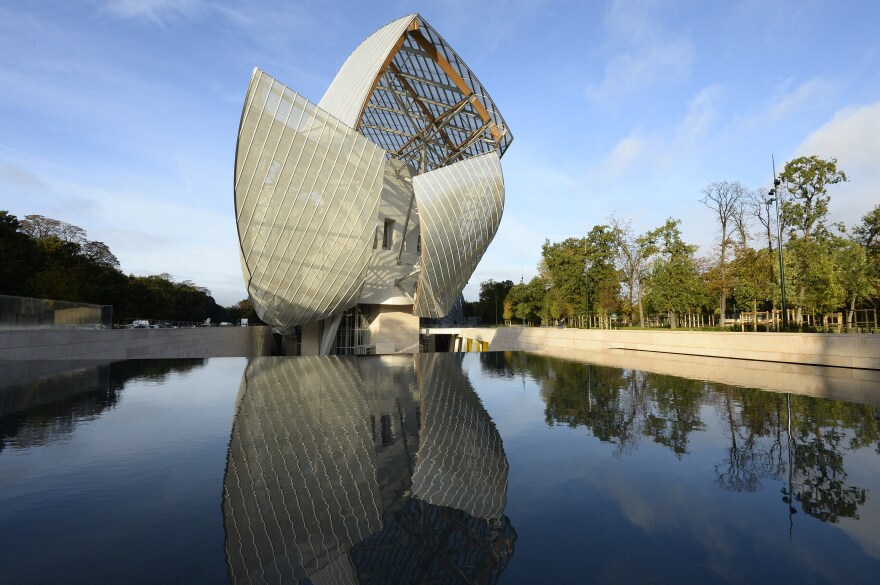

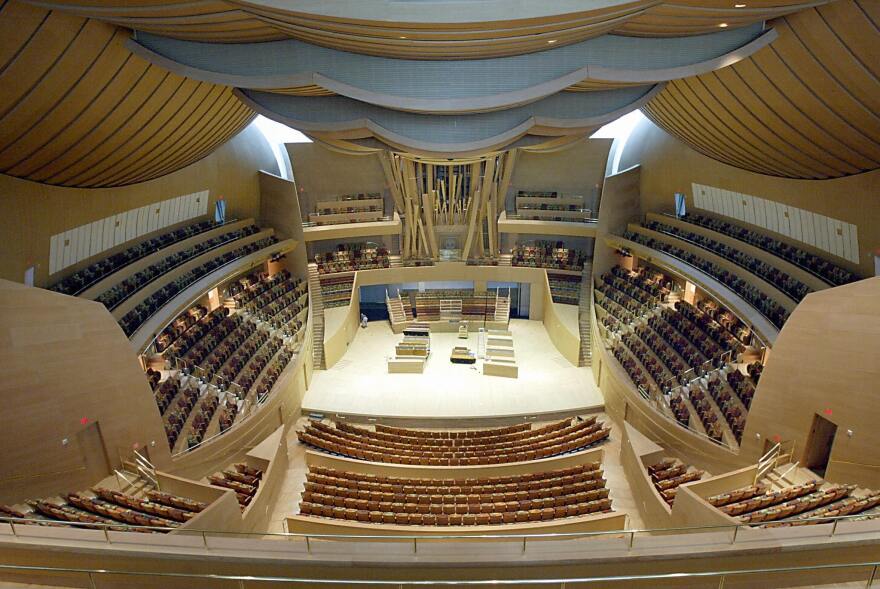

Floating, swirling, shining, sculpted, Frank Gehry created buildings we had never seen before. The architect behind the Guggenheim Museum in Spain and the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles transformed contemporary architecture. He died Friday at his home in Santa Monica, California, after a brief respiratory illness, according to his chief of staff. He was 96.

Gehry won every major award – including the Pritzker Prize and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. When the American Institute of Architects awarded him its gold medal in 1999, Gehry looked out at an audience that included contemporary building gods like Philip Johnson, Robert Venturi and Michael Graves and said, “It's like finding out my big brothers love me after all.”

“He was probably the only truly great artist I ever met who cared deeply about what people thought of him and made sure people loved his work,” says Gehry biographer Paul Goldberger. The architect received his share of criticism – “accusations of designing crazy shapes and not paying attention to the budget.”

But the praise was louder because his striking buildings made people happy.

Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images

/

AFP/Getty Images

Bertrand Guay/AFP/Getty Images

/

AFP/Getty Images

“I've always been for optimism and that architecture shouldn't be sad,” Gehry told NPR in 2004. “You know, a music and performance building should be enjoyable. It should be a great experience and it should be fun to go to.”

There was exuberance in his work. The swoops and whirls made possible by aerospace technology lifted the spirits of viewers accustomed to postwar modernism—austere, boxy buildings of glass and steel that seemed imposing and forbidding.

Gehry says he found this style cold, inhumane and lifeless. “I thought it was possible to find a way to express feelings and humanistic qualities in a building,” Gehry said. “But I didn’t realize it until I randomly started experimenting with fish shapes.”

He loved the shape of fish and the way they moved. He drew them throughout his life, an inspiration that began in his grandmother's bathtub in Toronto.

“Every Thursday when I was at her house, I went to the market with her,” he remembers. “And there was a big bag full of water that we carried home with a big carp in it. We put it in the bathtub. I sat there and watched, and the next day it was gone.”

These carp were made into filtered fish – a classic Jewish dish – but remained in Gehry's memory long after dinner. He translated their curves and movements into architecture. In Prague, Czechs call his elegant design for an office building “Fred and Ginger” – two cylindrical towers, one solid, the other glass, pinched at the waist, like dancers. His Disney Hall and Guggenheim Museum swell like symphonies.

/ Tony Hisgett via Flickr Creative Commons

/

Tony Hisgett via Flickr Creative Commons

“He really wanted you to feel a sense of movement,” Goldberger says. “A building is a static thing, but when it feels like it’s moving, that was more exciting to him.”

The Guggenheim – a billowing vortex of titanium in gold and sunset colors – wowed onlookers. After opening in 1997, Gehry said everyone who came to him wanted a Guggeinheim. But Gehry wasn't interested.

“Like all great artists, he wanted to keep pushing himself and moving forward,” says Goldberger. “He didn't want to copy himself. He didn't want to do this building again.”

The Guggeinheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain and Disney Hall in Los Angeles (opened in 2003, a silver stainless steel swoosh, 1/16 inch thick) are Gehry's signature buildings. But they are a far cry from his early works. His own 1978 Santa Monica residence is furnished with ordinary materials. If customers couldn't afford anything special – marble, for example – he would use cheap material.

Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images

/

Getty Images

Hector Mata / AFP/Getty Images

/

AFP/Getty Images

“He started using plywood, chain-link fencing and corrugated iron,” Goldberger says.

These buildings attracted attention. But the later ones made him a star – and a term was coined: Starchitect. Goldberger says Gehry hated it.

“He didn’t really hate fame,” Goldberger explains. “But he was too smart to sacrifice everything for that.”

Gehry stayed true to his vision. He turned down commissions that didn't feel right and imagined others that would be built, widely admired, but sometimes not what he wanted.

“You know, what I have in my mind’s eye is always ten times better than what I’ve ever achieved because the dream image can seep through…” Gehry said with a laugh. “But in terms of public acceptance, it's beyond anything I ever expected. I've never been accepted like this before.”

Gehry received a National Medal of Arts from Bill Clinton and a Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama. The New Yorker called Bilbao “a masterpiece of the 20th century.” Architect Philip Johnson called it “the building of the century.” And the audience (with some exceptions, of course) was delighted with the work.

“He made great architecture accessible to people,” Goldberger says, and that reshaped their ideas about what buildings could be.

He describes Gehry's work as “one of those extraordinary moments when the most progressive art intersects with popular taste. That happens very rarely in culture and in any field.”

It is said that architecture is the message that a civilization sends into the future. With molded and sculpted walls and buildings that appear joyful and free, Frank Gehry's message is one of humanism and hope.

The author of this obituary, Susan Stamberg, died October 2025. The story was updated and verified before publication.

Shannon Rhoades edited the audio for this story. Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

Copyright 2025 NPR