When architect Rich Hostelley first inspected the parcel for Janice Fleming's Woodstock estate, he saw more than just dimensions and setbacks; he saw a place with history.

Fleming envisioned replacing her aging garage with a taller, two-story building with living space upstairs. But Hostelley, an architect whose practice spans projects throughout the United States and the United Kingdom, immediately recognized that erecting a large new building on the small site would dwarf the century-old house already rooted there.

Whatever he designed, in his opinion, had to feel like it belonged.

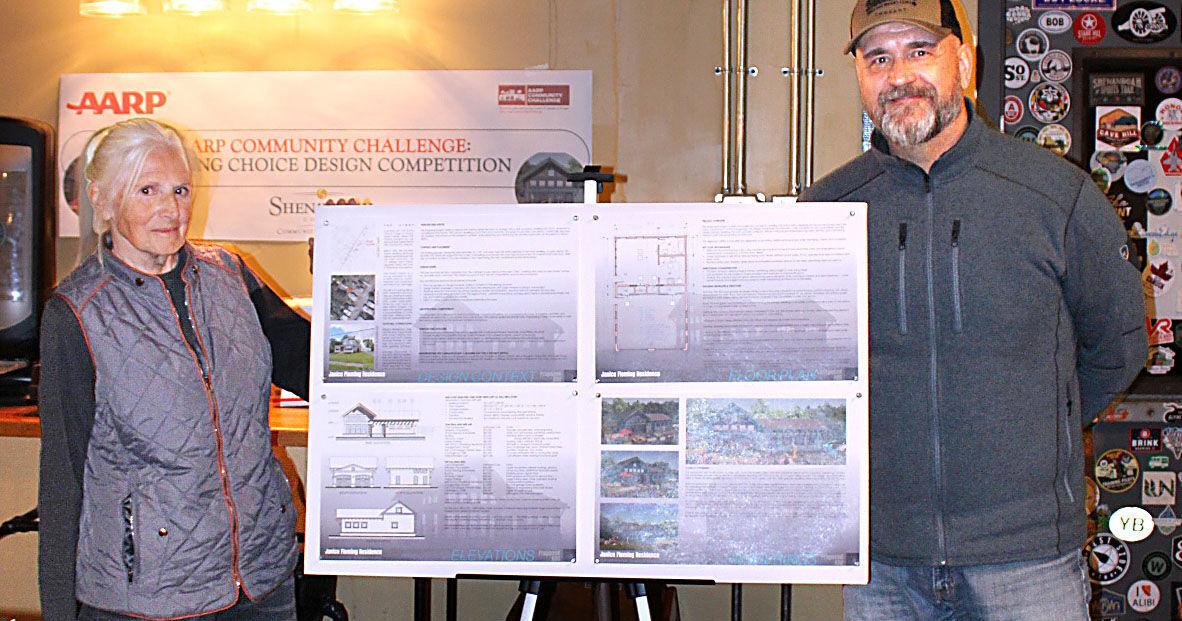

His solution — a compact garage replacement with a raised sleeping platform and exterior details borrowed from Woodstock's older homes — ultimately won two awards in Shenandoah County's inaugural Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) Design Challenge: Best Adaptive Reuse and the People's Choice Award.

Instead of reaching for something flashy, he designed something familiar. In a county where architectural continuity is part of the landscape, this calm approach was well received.

Shenandoah County launched the ADU Design Challenge this year with a simple question: What might tiny homes look like if they were designed specifically for Shenandoah County? To run the competition, the county received a $20,000 AARP Community Challenge grant, pairing architects with local homeowners who volunteered their properties as real case studies.

Instead of sketching out ideas for theoretical properties, the designers confronted the full reality of Shenandoah County's housing stock—aging garages, narrow backyards, historic districts, unusual setbacks and homes whose owners were already thinking about how to age in place.

The goal was not to create plans ready for approval. It was about showing the residents what was possible. As more families care for aging relatives, more young adults are paid out of rent and more long-term homeowners hope to stay put, county planners wanted concrete examples of how ADUs could fit in without detracting from the character of Woodstock, Strasburg, Mount Jackson and surrounding towns.

The submissions ultimately formed a small gallery of potential futures: a courtyard cottage built for privacy, a universally accessible mini-home geared toward aging in place, and Hostelley's reimagining of a garage floor plan into something that feels both fresh and familiar. A jury selected the winners and residents cast their votes for a People's Choice Award.

A jury selected winners in five categories Monday evening at the Woodstock Brewhouse: Best new detached ADU went to The Veil by architect Julian Liang; Best Adaptive Reuse went to Rich Hostelley for his design on the Fleming property; the AARP Accessibility Award went to Sydney Tucker and Zhan Chen for their Core House concept; The People's Choice Award also went to Hostelley's design; and the student winner went to engineering student Levi Stutzman from Eastern Mennonite University for the Owen Remodel ADU.

The right fit

For Janice Fleming, the Woodstock homeowner behind Hostelley's award-winning design, the idea of an ADU wasn't new. She had already been thinking about replacing her dilapidated garage with a building that would provide living space for family members.

She had watched her mother grow older, lived comfortably with a relative, and had another family member build an addition to her home to care for a grandmother

“Needs are very individual,” she wrote in an email, “but for many people an ADU meets both housing and housing needs.”

Her property offered space for a small, separate unit, a place that could one day house a relative, support a caregiver, or serve as a rental property until her own needs changed. The focus was on flexibility paired with independence.

Living in Woodstock's historic district added another layer. Every new building had to take the surrounding houses into consideration. She didn't want a bulky new building that would compete with her 100-year-old house. She wanted something suitable.

When she saw Hostelley's design, with its modest rooflines, preserved floor plan and craftsman-like details, she was immediately drawn to it.

“The design fits harmoniously with my property,” she said. “It recognizes the historic features and character of the area.”

Aging in place

While Hostelley's design won over residents with its familiarity, the competition's winning detached ADU took a completely different direction.

Designed by Julian Liang for Syed and Mrs. Raza's Strasbourg estate, “Veil” built its identity on something that is harder to achieve on a compact property: privacy, openness and accessibility at the same time.

The Razas were drawn to competition for a deeply personal reason.

“My wife and I had talked a lot about aging in place when we bought this house,” Raza said. “It’s a two-story house and we kept wondering what life would be like in five or 10 years if stairs became an issue.”

Submitting their property seemed like a rare opportunity to imagine alternatives without leaving the community they love.

Liang designed the ADU around a carved courtyard, an outdoor space that anchors the entire design.

“It creates a visual buffer, brings natural light deep into the floor plan and allows the interior space to expand outward without increasing the footprint,” he said.

The signature move is the sliding privacy veil, a system of mesh barn doors under a mesh roof that allows residents to alternate between openness and seclusion. Liang said it is the perfect solution between privacy and neighborly connections.

“It gives us quick access to the outdoor area,” Raza said. “And the barn door fence allows the outdoor area to become part of the living area, which is our favorite feature.”

The Veil was designed entirely on one level, with barrier-free entrances and wide circulation arches. It was created with long-term mobility in mind, a plan that could one day see the Razas take over to age in place.

“Zoning and cost would be the two hindering factors, but if we could overcome those, this plan could provide us with several benefits,” Raza said. “Not only as an aging-in-place solution, but also as a guest or carer’s suite or as a potential source of rental income.”

Small room

The third winning design, Core House, designed for Olivia Hilton in Mount Jackson, rounded out the trio with a focus on lifelong accessibility. Designed for a property in Mount Jackson, the design focuses on universal access: a single-story plan with wide circulation routes and adaptable spaces designed to support aging in place.

Even without comments from the design team, the drawings make the intent clear: a compact home designed for residents today and decades from now.

For Hostelley, this purpose-driven approach reflects the broader value of ADUs.

“The ADU market gives people a greater sense of belonging,” he said. “It's theirs. It gives them the opportunity for financial stability, but also creates a community for themselves that they can include people in. Those people then feel like they're part of something.”

Creating community does not have to compromise with neighborhood culture, Liang said.

“ADUs can be more than just secondary structures, they can be beautifully designed homes that don’t impact the quality of life,” Liang said.

The Future of Shenandoah County

Taken together, the winning designs suggest where the housing debate in Shenandoah County could be headed. Each project approached its location differently, through historic character, courtyard privacy or lifetime accessibility, but all three are based on the same idea: Tiny homes can help people stay close to the places and relationships that matter.

For Fleming, that means the ability to age close to family without changing the rhythm of her historic neighborhood. For the Razas, it's a chance to imagine life on one level without leaving the community they love. And for Hostelley, it's a belief that ADUs can quietly restore connections that have been eroded by modern housing structures.

County officials will unveil new housing data and strategies on Dec. 4, but the design challenge has already answered a quieter question: Can a rural county add housing without losing what makes it home?

In Woodstock, Strasburg and Mount Jackson, the winning designs suggest the answer could be yes — if tiny homes are built with the same care as the old ones.

To view the various designs submitted, visit the Shenandoah County website at shenandoahcountyva.gov/514/AARP-Community-Challenge-ADU-Housing-Des