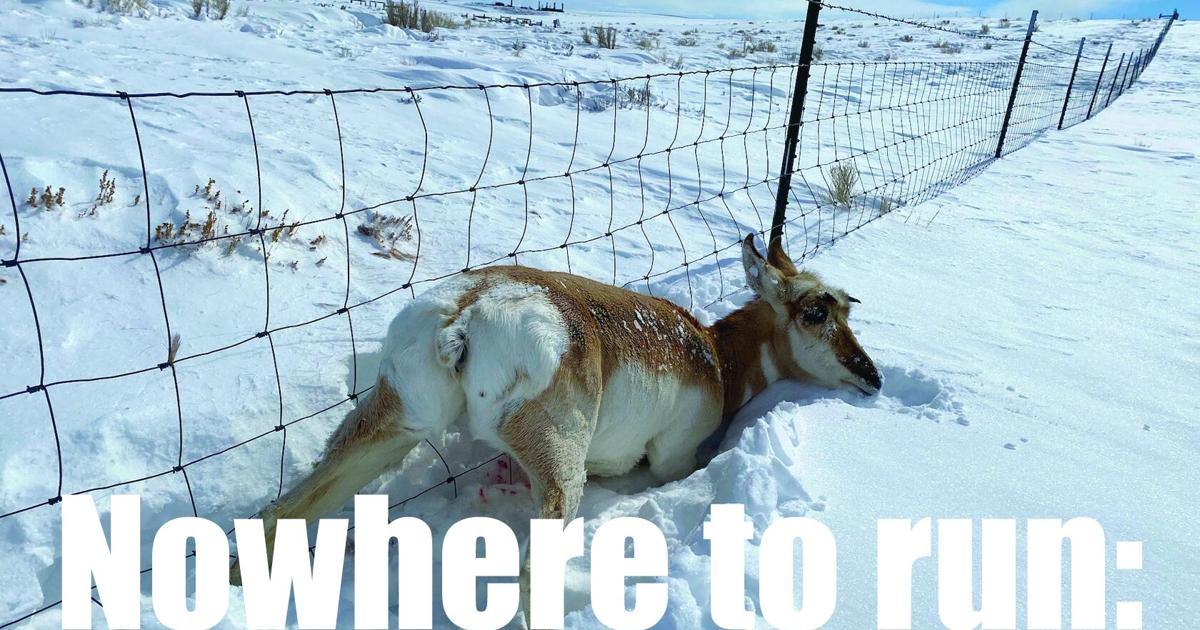

When a strict winter met Wyoming's red desert in December 2022, a Pronghorn deer made a desperate escape attempt and trudged 240 miles through a snow -covered wasteland.

Fences blocked her routes into a less snow -covered habitat and thwarted her ability to go out of the deep snow and add the time and risk of your search. Ultimately, she returned to the area from which she started where she died.

Usually Pronghorn can cover many miles a day with speeds of up to 60 miles per hour. In an open landscape, they were able to move out easily by successfully successful since the Pleistocene.

This time, however, the worst winter in combination with fence and street barriers for two decades, so that the fastest mammals on the continent have no way out. Pronghorn tried to make escape movements to find more hospitable habitats. At the end of winter, half of the Pronghorn died in a stronghold of her range.

An interdisciplinary team of scientists who works at the interface of computer, data science and wildlife ecology from Wyoming and Germany used a wealth of GPS data to publish a post-mortem over the failed escape of the prong horns. The study was published online on April 1 and is the cover story for the issue of the Journal Current Biology on April 21.

The results underline how important it is to restore the connectivity to secure extreme weather events that are becoming increasingly common.

“When you see the movements of this pencil horn, such a clear picture of a struggle for flight,” said Ellen Aikens of the School of Computing and the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources at the University of Wyoming, the main author of the paper. “It was really sober to see how a prong horn was hung on fences, while others were followed by 80 miles on Interstate.”

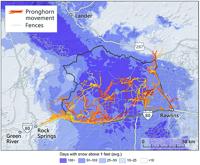

Through maps and spatial analyzes, the scientists found that barriers made by humans and long-lasting deep snow synergies and composed, which led to a collapse of the connectivity of the habitats during the season.

The researchers identified fence barriers for 20 miles long, where Pronghorn could not find a way. In other cases, Pronghorn tried escape routes that corresponded to the Interstate 80 for 50 miles, and looked in vain for a way to cross the street with less snow into areas.

In the course of winter, the barriers were delayed, the access to the access of the habitat, their escape from deep snow and burned their fat reserves.

Until February 1, Pronghorn was scattered in the snow and along the fences to wait the winter where they were or succumb.

Overall, the researchers were able to determine how barriers and snow together lead to a 3.7-fold increase in the Pronghorn mortality compared to the survival rates from previous years.

A well -coordinated study

A map of the long-distance movements of Pronghorn in the red desert of Wyoming in the winter of 2022-23. Alethea Steingiser, Infographic Laboratory of the University of Oregon

By chance, GPS neck bands were already equipped with Red Desert Pronghorn when the difficult winter hit at the end of 2022. So the project was able to monitor Pronghorn during and after the hard winter.

The research team has linked satellite data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center of the University of Colorado Boulder with a GPS data set of 33 Femal Femalhorn Callart by Biologie Hall Sawyer, a researcher with western ecosystem technology.

The snow packaging was 101 days lower than one foot. 60 percent of the approximately 3,400 square miles in large desert herd unit were covered or more covered in this depth or more. This was due to 2004, which corresponded 4.2 times the average annual snowfall and an 18.3-fold increase in the number of weeks with a snow packaging at this level.

The red desert sees average less than 10 days of such snow shines. In 2022-23, the snow duration was comparable to parts of the nearby high limit, a place that clears the hoofs during its autumn migrations.

Fighting in unknown countries

Almost the entire prong horn in the study made escape movements and traveled from 21 miles to 248 miles. Two prong horn that had not tried to flee died. Most of these animals were in motion until January 2, 2023 when the average snow depths reached a foot.

The escape movements brought Pronghorn on unknown terrain in front of well -known seasonal areas and migration routes. This meant that the animals had to spend a precious time to negotiate with romance fences and streets, which had to expose deep snow and lack of food for longer periods.

Streets were a big barrier for their escape. The Pronghorn, which moved south and west, came across the Interstate 80, which completely blocked her movement in areas with less snow on the other side of the highway in an area south of Point of Fels.

Nobody could cross the 14 -prong horn that corresponded to the intergovernmental route over long distances. Individual animals spent up to 20.9 days within 550 meters from the highway and moved to 47 miles along the street.

In contrast, seven of the eight prong horn, which moved to the east and north to the US Highway 287, were able to cross, although they were also held along the street for one to seven days.

Fences caused even more trouble. Pronghorn, who tried to escape, hit an average of 18 fences, which delayed an average of seven days. The discussion of a fence under snow -covered conditions increased the number of delay days compared to the previous year, when fences only delayed it by three days. A escape with a barrier was stopped every day, almost an additional day in deeper snow.

The overall removal covered had no influence on the probability of death: Pronghorn is born to guide and cover large amounts of the terrain. Instead, the main factors for increased probability of mortality that were deeper than one meter and initiated an escape later in winter.

For every week after the beginning of severe conditions, for which a prong horn was waiting to start his escape, it died 4.7 percent higher.

Not all fence barriers were the same. Most fences were half -translucent, but some were almost completely impassable. A fence block in the Red Desert Castle Pronghorn over an area of 104,098 acres. As a reference, this is an area that is greater than the Yellowstone Lake, more than twice as high as the Washington area, DC or the triple of the San Francisco area. In view of an exclusion zone of this size, Pronghorn wasted precious time and energy to look for a way.

Rest) connectivity

The results underline how important it is to examine and show fleeing movements under extreme weather conditions and how harmful delays can be due to obstacles – and the need for nature conservation projects that restore connectivity.

Although the preservation of seasonal migration routes throughout the west gains dynamics, the study must concentrate on the elimination of impermeable barriers outside the usual routes that come into play during the escape movements.

Although rare, these movements are a question of life or death, with serious consequences for mortality and the maintenance of herds in the long term. The researchers see an urgent need for connectivity solutions.

“Measures to increase and maintain the landscape connection not only help to hike animals, but can also facilitate the safe passage for animals that escape extremely weather,” said Aikens.

The data analyzed in the study already helps to identify and finance a common effort in order to increase the connectivity in the red desert-and, as it is hoped, reduces the severity of the future mass mortality events.

In response to the first report by Sawyer and Andrew Telander about the data from 2024, public and private partners are retrofitting 24 miles fences in the western part of the red desert in order to restore access to thousands of hectares of hectares.

The employees of the 2024 project include a ranch family, the Wyldlife Fund, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust Fund, the Knobloch Family Foundation and the most important partners of the non -governmental organization. The effort is the subject of an upcoming film “Underlook: Making Space for Pronghorn in Wyoming's Red Desert”, which was produced by the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the UW.

Finding such solutions for these impermeable barriers in the long term helps to maintain Wyomings Pronghorn. The researchers expect the same approach to benefit the population of other hunger who are exposed to similar threats worldwide.

In addition to Aikens, co-authors of the current Biologie area Sawyer belong; Jerod Merkle from UW; and Wenjing Xu from Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Center in Germany. The financing of the study was provided by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and the Wyoming Migration Initiative.

A long -term problem

Among the big games of Wyoming, small bodied prong horn is the least in navigating deep snow that falls over the middle Rocky Mountains.

Short legs and small hooves are the Achilles. They flounder in snow drifts, the bison, moose and moose slightly plowing through or overlaping.

In order to compensate for your weakness in the snow cover, use speed and senses to explore and improvise your way to less difficult winter habitats.

Wyoming biologist, including Bill Hepworth and Rich Guenzel, have found how Pronghorn around Blizzards or strong snow cover between the red desert and colorado moves. In an open desert landscape, Pronghorn can rely on massive areas to search for wind -whipped areas or move many miles in one day to find areas with rain shadows in which snow did not fell so deep.

This centuries -old strategy has stalled in today's American west. For decades, biologists have observed how the red desert ends. The completion of part of the Interstate 80 in the 1960s followed from efforts to tan the sheepwear.

Many of these cattle pastures occurred in chess board countries along the historic route of the Transcontinental Railroad, whereby private and public areas were alternately monitored by the Bureau of Land Management. The dispute of the red border fence in the 1980s required the maintenance of the Konnonghorn connectivity in the chess board.

Although the red desert and the large divide pool still appear underdeveloped, these countries are crossed by two main cars and pebbles, several oil and gas fields and thousands of kilometers -long legacy cattle fences.

The high -density fence of these factors is the most important barrier for Pronghorn. In contrast to mules and elks, who can jump over fences, Pronghorn has great difficulty crossing woven fences to hold herds of domestic medschers and lambs together.

The researchers of the University of Wyoming, Adele Renking and Jeff Beck had previously recognized the barrier effects of grazing at the red desert. Reinking regarded the fence barriers as an even more important disadvantage for the habitat of the Pronghorn as the Interstate 80, which the UW researcher Ben Robb found that it is an almost complete barrier for the movement of Pronghorn over 400 miles of southern Wyoming.